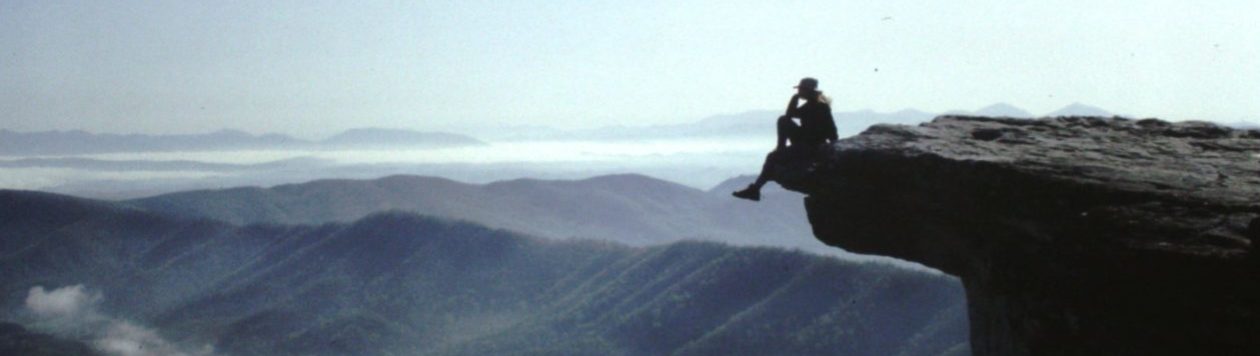

The Pacific Crest Trail runs nearly 2,700 miles, from Mexico to Canada, through the drylands and deserts of southern California, over the mountains of the Sierra Nevada, and through the Cascades of Oregon and Washington. Along the Pacific Crest Trail tells the story of a thru-hike of the entire route, including observations of history, environment, and geology, accompanied by the fabulous photographs of Bart Smith. The following excerpt finds the author in the Three Sisters Wilderness central Oregon.

.

Quite possibly, my favorite trail name belongs to a hiker a couple of weeks ahead: Andante. Andante is a musical notation generally translated as “slowly.” More accurately, it means “at a walking pace. It’s a great name for a music-loving hiker.

I find that often as I hike, my feet march in step to music played in my mind — andante — at a walking pace. Memory music, dredged up from some deep cranial cavity, as though the mountain air has whisked in and scoured out my brain, and now the debris is being expelled out my ears. I hear, in no particular order, folk music from summer camp, love songs from college, classical piano music drummed into my fingers from years of practice. Sometimes I sing, but only when my partner is far ahead or far behind, since he tends to say things like “Do they have moose in Oregon? I could swear I hear a moose.”

The definition of andante, I learn, can be stretched quite a ways if you take “walking pace” literally. On hills, my walking pace is a laborious crawl; Chopin’s “Funeral March” will do nicely. On a gentle flat stretch, I stroll easily to the first movement of Beethoven’s “Pastoral” Symphony. Once, Dave Brubeck’s “Take Five” played for a while, and I had to lurch along, fast, in five-quarters time. Often a tune stays in my head for days on end.

When memory music turns off, mountain music begins.

Water is the melody. High up, the water trickles and drips; lower down, it cascades and roars. Crossing over a creek that drains one of the peaks of the Three Sisters, I hear the water echoing against a nearby rock, and I wonder if it always echoes. Will this water sing to this rock for all eternity? Will the rock always answer?

Woodpeckers are the percussion section. You hear them far more often than you see them; they have the habit, like squirrels, of spiraling around to the other side of a tree trunk as you approach. Even if you stop the first minute you hear their telltale hammering, you’re unlikely to see them because their sound has a ventriloquist-like quality; it seems to come from nowhere and everywhere and you look the wrong way. Their calls, however, betray them; they sound like they belong in an Amazonian rainforest.

There are other bird songs: Let’s make them our wind section. Sweet chickadees singing their three-note song are the flutes; raucous crows, the trumpets. For our piccolos, we’ll choose the tiny peeping of baby grouse that are always scampering in panic along the trail.

I am part of the symphony, too: my breath as I climb, my footsteps on the rock, the click of my walking sticks.

And of course, the weather, an ever-changing accompaniment: Wind caressing grasses, rustling tree leaves, or gusting, whistling, howling. The muted patter of raindrops on pine duff. The determined, rhythmic splatter of an all-day downpour.

Musicians are fond of pointing out that as important as the notes are the silences in between.

At the end of a misty, wet day in the Three Sisters Wilderness, we bed down to the slow movement of the symphony. There is at first the soft tapping of rain on the tent, the murmur of the nearby stream, the occasional thump as wind knocks down rain that’s been collecting on a tree branch. We hear the gentle breath of a chill wind clearing out the rain.

Then, but for the stream, there is silence.

And in the morning, sun.