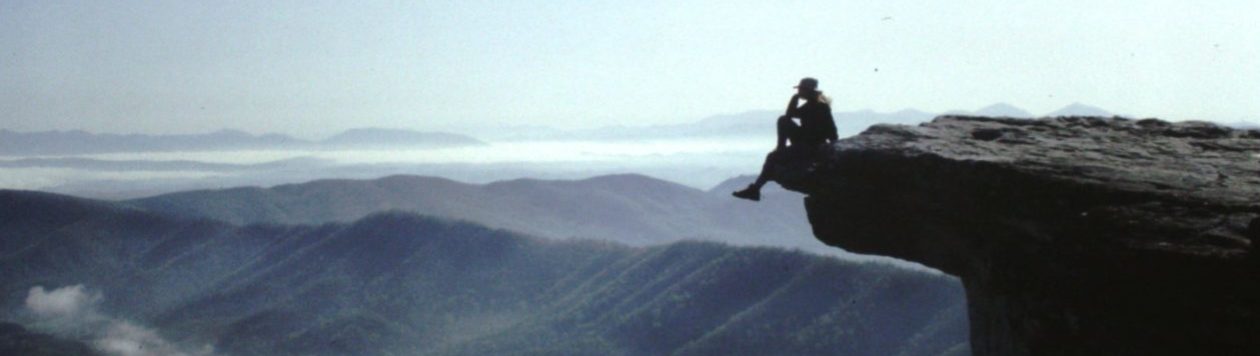

I also have a mock-up of the cover (though covers sometimes change between design and production; I am hoping this one does not.)

The book contains essays about more than 30 hiking trails organized into sections focusing on history, pilgrimage, wilderness, mountains, diverse environments, and long-distance trails. There are also shorter descriptions of another 50 or so noteworthy trails.

The text is full length – some 60,000 words — and the book is chock full of photography that almost leaps of the page to drag you along for a hike.

It is exactly the kind of book that made me cry with despair some 30 years ago, when I was a young editorial assistant at a company that published books about financial planning, insurance, selling real estate, and other subjects in which I had less than no interest.

I always get reflective around the new year, so I’ve been thinking about how things can turn around, even if it takes a long time. This post is what I wish someone had told me back then: If you are passionate about a creative career dream, if you are frustrated because the path ahead is murky, cluttered, and sometimes damned unpleasant: keep going with all your art. Develop the right skills. Work as though it’s the only thing that matters. Where you are now is not where you will be forever.

I remember my melt-down moment: I was working in Chicago, and there was a beautiful independent bookstore called Stuart Brent’s. Brent’s was a lunch-time hangout for me. Virtually everything in the store reflected the best of book publishing – books as works of art. The books focused on art, design, photography, nature, history, fashion, art, and travel. You wouldn’t go there to find a Dummies book or a paperback romance.

Making typical editorial assistant wages, I could barely afford to buy anything in that store: The books featured in the window and in the front cases were in the $60 – $80 price range, and this was back in the late 80s. But being a fairly typical editorial assistant – in it for love, not money — that didn’t stop me from spending money I didn’t have.

Browsing, of course, was free.

I would have happily worked on any book that store ever sold. I would have been delirious to get a job at any publisher they carried.

Instead, I was working on cheaply made, shoddily produced books with two-color covers and clunky designs on how to sell insurance or get licensed for real estate. Chicago was not then and is not now a hub of book publishing. The publisher I worked for was one of only a half dozen or so shows in town. None of them produced the kinds of books that would be found at Stuart Brent’s.

Going to Brent’s at lunchtime only seemed to make things worse as I considered the irony of being surrounded by hundreds of books on scores of topics I was interested in, only to have to go back and shepherd another book on business through its hurdles.

I think that as far as my bosses were concerned, the career path ahead of me was well-lit and obvious. I seemed to be well-enough-liked by the various managers, had managed to keep my opinions about business books to myself, and had been promoted several times. But I didn’t want to go where that path went.

The path between then and now wasn’t something I had much control over: An ad in a publishing magazine led me to a job in environmental publishing in Washington D.C. Island Press did not publish the kind of books you’d find in Stuart Brent’s, but they focused on environmental issues, a subject I was intensely committed to. Marriage took me away from that job and into a world of long distance backpacking. Combining my interest in travel and publishing, I became a book author. It’s not a path I would have predicted.

Today, nearly 30 years later, I’m the author of 17 books, some of which would have found a home in Stuart Brent’s – and some of which would not. Part of growing up is learning when to compromise, when to suck it up and pay your dues, when to sign the bad contracts, when to walk away, and when to follow your heart.

My most recent book, America’s Great Hiking Trails, squeaked onto the New York Times bestsellers list in travel and won a Gold Lowell Thomas Award. This next one: Great Hiking Trails of the World, is exactly the kind of books that would have brought tears to my eyes with longing – to go to those places, to write about them, to edit a book about them – anything.

We all have to find, and sometimes forge, our own path through the publishing thickets. Many authors, like me, bounce between editing gigs and writing gigs, sooner or later finding their feet in one or the other. Our journeys are all different, but looking back, I see a couple of patterns that I think a lot of us have in common.

- Being true to yourself. I knew I didn’t like business books, so I kept doing the things I did like: Playing piano, traveling (as much as possible), volunteering as a leader of a local inner city outings program, editing a local environmental publication, attempting to write a novel. Showing up whenever I could in the subjects I was interested in meant that when opportunities arose I had more to offer than my work experience: I had passion.

- At the same time, there is a time to shoot the moon, and there is a time to lay the groundwork. I didn’t like my business publishing job, but I did it as well as I could. As a result, I developed skills that qualified me for a more satisfying job.

- Show up for your life. You never know what opportunities are lurking around the corner. For example, my (failed) novel landed an agent, who placed my first non-fiction travel book.

- Develop your people networks. It’s best to do this when you can offer something rather than when you need to ask for something. Join a professional association and volunteer to run the seminar program, run for office: anything that connects you with others in your field. Remember that favors and support you give will be returned, though not always in ways you expect or can predict.

- Develop your skills. I don’t care what skills: Take classes, attend seminars, form a writing critique group. They all come in handy.

Mark Twain once wrote that the “reports of my death have been greatly exaggerated.” The same, I believe, is true for publishing. Certainly, people have been talking about the death of publishing since I’ve been in it, and that’s more than 30 years. But the human connection to stories and information is as strong as it ever was, even if how we take delivery has changed. Waiting my turn in the doctor’s office this morning, I noticed that every other person in the waiting room had their nose buried in a book.

Publishing still chugs along. At its core, it is an industry that rewards passion married to skill. It also rewards sticking with it, following a dream, and trying to see our old world through new eyes.

Stuart Brent’s is long gone. But they would have carried my most recent book. And my next one. I wish I could reach into the past and tell that young editorial assistant that.